A study combining history, economics, and fluvial geomorphology examines the causes of the adoption of coal power during the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain. At the beginning of the mechanization of the textile industry in Britain, most machines were powered with waterpower. Eventually waterpower was replaced by using coal to make steam power and the causes of this shift have long been debated. One influential hypothesis has been that waterpower became scarce in the industrial heartland of northwest England during the early 19th century, as all available suitable sites were already fitted with watermills. To test that hypothesis, Tara Jonell and colleagues evaluated the availability of waterpower resources across mainland Britain during the water-to-steam transition, which spanned about 1770–1840. The authors used 19th century climate and meteorological observations as well as a cartographic mill census data as inputs to geomorphological flow-routing to estimate river discharge and waterpower potential. The authors conclude that on a national scale, waterpower remained significantly underutilized, but that at key local scales, such as the major cotton textile production region north and east of Manchester, sometimes called “Cottonopolis,” waterpower was scarce by 1838, if not earlier. According to the authors, limited waterpower should be considered one of the major drivers that encouraged the adoption of the use of coal for steam power by area manufacturers.

PNAS Nexus

Limited waterpower contributed to rise of steam power in British “Cottonopolis”

16-Jul-2024

Additional Media

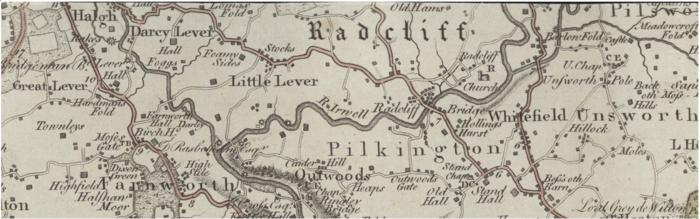

Early county maps offer one of the richest and arguably most comprehensive cartographic sources of industrial location information for Britain in the late 18th to early 19th centuries. The study authors used over 140 early county maps made by an array of amateur and skilled mapmakers to identify the distribution of mill sites during the early Industrial Revolution. Watermills were often indicated on early county maps with waterwheel symbols (small circles with radiating spokes or vanes). Map sou Credit: National Library of Scotland

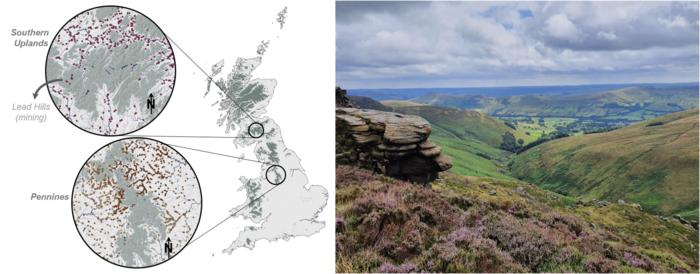

Mills (circles in left) were rarely sited above 300 meters elevation or on land broadly classified as moor, peat, fen or marsh (green area in left; upland landscape in right). The very few sites above 300 meters were commonly associated with mining activities. The more than 90% of mills sited below 200 meters elevation took advantage of the generally greater and more regular waterpower available there and maintained stronger links with populated villages surrounded by better transport networks. Credit: Tara N Jonell.

Many water-powered mills did not require very large falls of water to generate power, such as famously seen at (A) New Lanark on the Falls of Clyde (River Clyde, Lanarkshire). River meanders were creatively engineered, and the fall (and thus power) could be maximized by amplifying bedrock ledges exposed in the north of Britain. (B) Burrs Mill (River Irwell, Lancashire), a late 18th century cotton spinning mill, utilized upstream river meanders and a weir built across a natural waterfall formed b Credit: Tara N Jonell